Project Description

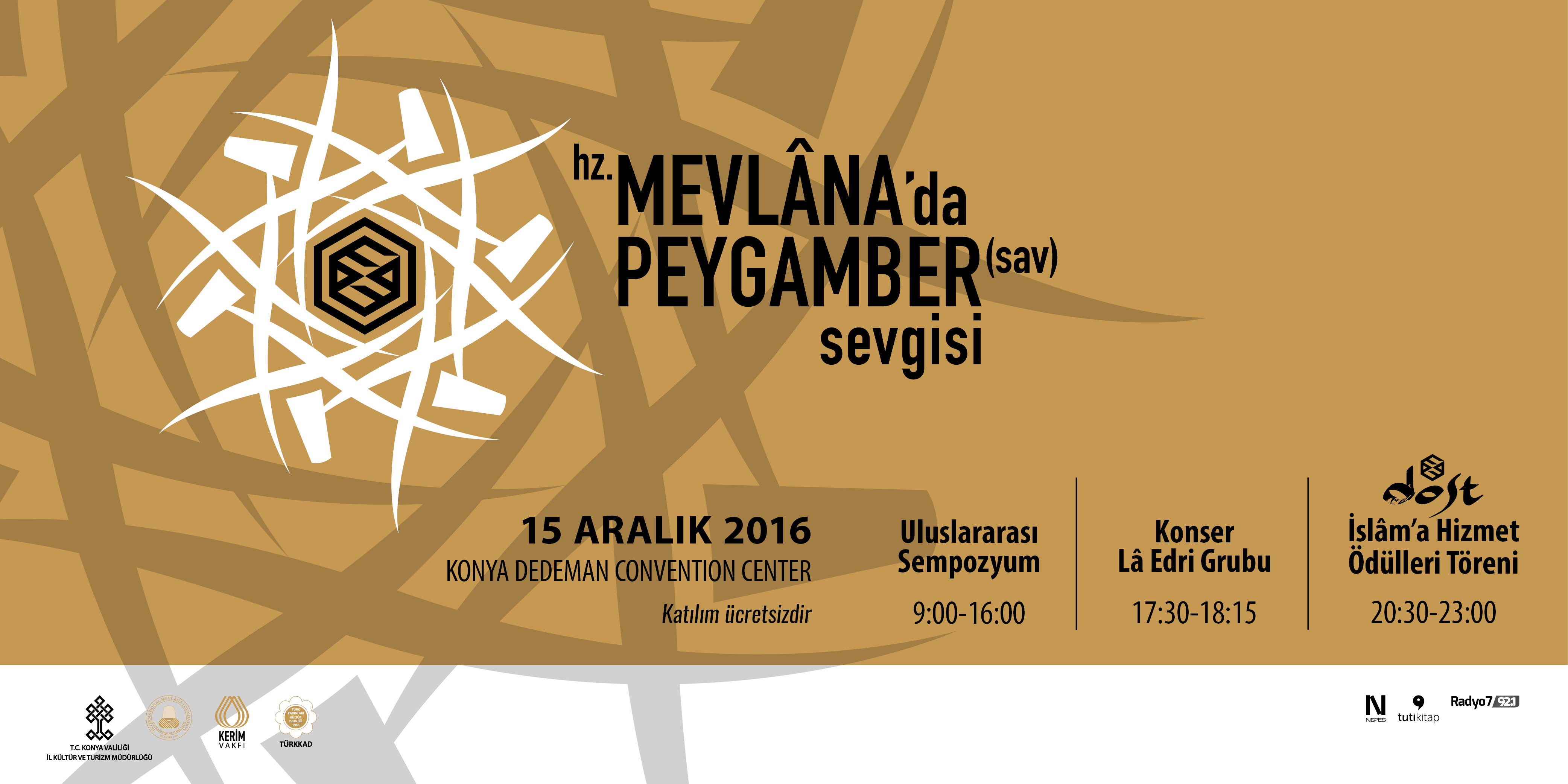

“Love of the Prophet in Mevlana” Title 13. DOST Awards for Service to Islam Presentation Ceremony

On the occasion of the Mawlid Qandil coinciding with Shab-i Arus, the Symposium titled “Prophet Love in Hz. Mevlana” and 13. The presentation ceremony of the DOST Service to Islam Awards will be held on December 15 in Konya.

The Prophet, who was sent as a mercy to the worlds. The 13th “DOST” Service to Islam Awards, which are given every year to commemorate the anniversary of the birth of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and his love that unites everyone under the banner of tawhid, will find their owners with a ceremony to be held in Konya on December 15, 2016 under the name of “DOST” Service to Islam Awards.

“Hz. Love of the Prophet in Mevlana” The 13th “DOST” Service to Islam Awards, which will be presented at the night to be organized under the title of ” DOST”, will be given to Prof. Dr.Süleyman Uludağfrom Turkey and Muhammad Iqbal from abroad.

After the opening speeches at the award ceremony, Prof. Dr. Mahmud Erol Kılıç “Hz. Mevlana will give a speech titled “Love of the Prophet in Mevlana”.

AWARD CEREMONY DATE: Thursday, December 15, 2016

AWARD CEREMONY LOCATION: Konya Dedeman Convention Center, Symposium Hall

***Symposium Live broadcast is realized by Nefes Publishing House Inc.

Muhammad, IDBAL

(1877-1938)

Indian Muslim Thinker, Poet

He was born in Siyalkut, near the Kashmir border in the Punjab province. Although there are different information about his date of birth, he recorded in his doctoral thesis that he was born on 2 Zilkade 1294 (November 8, 1877). His father Nur Muhammad, who was a Sufi mystic, and his mother Imam Bibi had a significant influence on the development of his religious personality. He received his primary and secondary education in Siyalkut; in 189S he took courses in philosophy and law at the Government College in Lahore. Two figures are known to have left lasting impressions on Iqbal during his upbringing. The first of these was Mawlana Mir Hasan, from whose wisdom and guidance he benefited since childhood, and the other was his teacher Thomas Arnold. Arnold recognized Iqbal’s talent and arranged for him to attend Cambridge University (1905). In Cambridge, Iqbal met the famous Hegelian philosopher Mc Taggart and the psychologist James Ward and studied philosophy, especially under Mc Taggart. Meanwhile, he became close to the orientalists Reynold Alleyne Nicholson and Edward Granville Browne. After completing his studies at Cambridge in 1907, he went to Munich, where he earned a doctorate in philosophy with The Development of Metaphysics in Persia , which he completed under the supervision of Fritz Hommel. Iqbal then returned to Lahore and taught English and philosophy at the Oriental and Government colleges for two years. Although he made his living largely as a lawyer, he never considered this work, which he continued until 1934, as his main interest.

The situation in the Islamic world led Iqbal, like other Indian Muslim intellectuals, to the idea that Islamic nations needed a renaissance. In 1922, he was given the title of “sir” by the British administration, but he did not use this title. He was a member of the Punjab Legislative Council from 1926 to 1929. In 1928-1929, he gave lectures on the re-establishment of Islamic thought at the universities of Madras, Hyderabad and Aligarh. In 1930, he presided over the annual meeting of the Muslim League of India in Allahabad. The first serious step towards the establishment of the independent State of Pakistan was taken with the ideas Iqbal put forward in the opening speech of this meeting. In 1931, the Second World War was held. He was appointed vice president of the World Islamic Congress at the International Islamic Conference. In 1931, the Second World Conference was held in London to discuss the issue of granting limited freedom of government to the people of India. Iqbal attended the Round Table Conference, where he was in close contact with Muhammad Ali Jinnah. On his way back, he visited Italy and Egypt and participated in the World Islamic Council meeting in Palestine. In 1932, the III. He attended the Round Table Conference and after the meeting he traveled to Paris to meet with Henri Bergson and Louis Massignon. From there, Iqbal traveled to Is pania, where he visited the Ulucami of Qurtuba and prayed in the mosque after obtaining permission with difficulty, which became an unforgettable memory. He wrote a poem about this titled “Masjid-i Kurtuba”. From Spain, he went to Italy and met with Mussolini and asked him to treat the Muslims of North Africa well. In 1933, upon the invitation of King Nadir Shah of Afghanistan, he traveled to Kabul with Suleiman Nedvi and held talks on the reorganization of Afghanistan’s administrative system. Iqbal contracted laryngeal cancer in 1934 and lost his voice, and later his eyesight also weakened. He started having financial problems. Nevertheless, he remained interested in the affairs and future of his people and the Islamic world. He died on April 21, 1938 and was buried at the foot of the minaret of Masjid-e-Shahi in Lahore. Muhammad Iqbal had three marriages and his son from his second marriage, Javid Iqbal, made important efforts to promote his father’s works and thoughts. Muhammad Iqbal is one of the most widely studied, researched and published Islamic thinkers of the last period. An Iqbal Academy was established in Karachi, which has been publishing a journal, Iqbal Review, since 1960. In addition, scholarly meetings are organized in various countries, especially in Pakistan, on various occasions, especially on the anniversary of Iqbal’s death. His grandsons Munib Iqbal and Walid Iqbal continue this work with great care.

Literary Direction: Iqbal made a name for himself in his country as a poet at a young age. “Himalaya”, “Orphan’s Cry”, “Candle and Butterfly”. The main subject of his lyrical poems, mostly in ghazals, including verses such as “Terane-i Hindi”, is India with its nature, people and history. Hence, poems with a patriotic spirit have been of great interest among Muslims as well as other Indians. Iqbal’s writings after his return to his country from Europe are seen to deal with religious and philosophical issues with increasing intensity. After his Urdu poems titled “Shikwa” in 1911 and “Cevab- ı Shikwa” in 1912, he reached the peak of his fame with his long elegy titled Esrar-ı Hôdi published in 191 S, followed by Rumuz-i bi-Hôdi. As a result of his admiration for Mevlana Jalalaluddin Rumi, he wrote both works in Persian in the style of Meşnevi-i Ma’nevi, and although he dealt with philosophical subjects, he managed to preserve the intensity of emotion. Iqbal’s turn to Persian not only allowed him to appeal to a wider audience, but also united him with a long tradition. Iqbal. In his poem Peyam-ı Meşrık, which is considered a response to Goethe’s divan (West-oestlicher Divan), he returns to lyricism. Cavidname, written in 1927, is considered his masterpiece; the Persian-language work is a kind of verse drama. Iqbal says that clarity in poetry is not essential, and even ambiguous elements in poetry can be useful in influencing the world of emotion. But it is possible to characterize his understanding of art as “functionalism”. Art should give life to man and society, strengthen the self, and, like the staff in the hand of Moses, destroy the false and reveal the truth (The Rod of Moses, pp. 60, 73). His poetry has one main goal: To teach Muslims to develop their personalities and regain their strength, both as individuals and as a community.

Understanding Science, Philosophy and Religion: Iqbal saw science, philosophy and religion in close relationship with each other. The conclusions of science are public and verifiable. Thanks in part to science, it is possible to predict and control events. With the constant development of science, people’s views change, and there is a constant process of reconstruction in philosophical and religious thought. Philosophy, as a free research activity, is skeptical of all kinds of authority; its function is to get to the bottom of the judgments and assumptions that human thought accepts uncritically and to uncover the reasons for their formation. According to Iqbal, religion also falls within the field of philosophical research, but philosophy, in making judgments about religion, must acknowledge its central place and recognize its function in the process of thought-based composition. Philosophy, which clings to a rational and intellectual point of view, looks at reality from a distance because it does not want to go beyond the world of concepts while trying to fit all the richness of experience into a system. Religion, on the other hand, gives us the power to make the truth almost melt within us. In the final analysis, philosophy is a theory and religion is a life. Unlike science and philosophy, religion seeks to understand and interpret the whole truth. In order to succeed in this, it has undertaken the task of combining and fusing all the data of human experience. Science tries to capture the observable side of reality, religion tries to capture the essence of reality by making use of these observations. The field of experience interpreted by religion (religious experience) cannot be reduced to any field or data of science. For Iqbal, religion is both emotion, doctrine and activity.

Re-establishment: Iqbal, who had a dynamic and organic understanding of philosophy, thought that it was necessary for Islamic countries to engage in a reestablishment activity in areas such as the individual, society, and theoretical thought. Because religious thought in Islam has lost its dynamism, especially in the last five centuries. In the face of the great developments observed in our time, the re-establishment of religious thought in Islam has become an indispensable task. There are two important phases to fulfill this task: The analysis and criticism of the traditional structure and the reconstruction of contemplation in the light of developments. In this framework, Iqbal criticizes the Islamic tradition and points out the aspects of classical theology and philosophy that are incompatible with the spirit of the Qur’an. In this way, he tries to bring the experiential and rational aspect of revelation back to the forefront. He then turns the same critical gaze to the tasvwufa, stating that he has not been able to come up with anything new by utilizing modern thought and experience, and that he is still continuing his outdated methods. The thinker, who reviews Islamic law and its main principles with the same approach, tries to reinterpret the Qur’an and Sunnah in the light of new developments and needs, and argues that unless the activity of ijtihad is resumed, both Islamic thought and religious life cannot be revitalized.

His Interest in Turkey and Turks: Iqbal, who was interested in the recent troubles of the Turkish nation, expressed this interest as early as 1911 in a poem he wrote for the martyrs of the Tripolitan War. Here, Iqbal is in the presence of the Prophet. When the Prophet asked him what he had brought as a gift, he said that he had brought a gift not even found in paradise and presented the bottle containing the blood of Turkish martyrs to the Prophet. Iqbal praised the Turks as the only Muslim nation that was able to preserve its independence during the colonial period, but he also saw them as having the potential to realize the “Islamic Renaissance”. The role of Turks in the history of Islam and the Tripoli Balkan. 1. Iqbal admired their heroism in the World Wars and the War of Independence and hoped for the future. The abolition of the sultanate and the abolition of the caliphate were also applauded by Iqbal and considered as a courageous jurisprudence within Islam. According to him, among Muslim nations, only the Turks have been able to break free from the lethargy of dogmatism and have made progress in renewing themselves with a consciousness of intellectual freedom. However, although Iqbal wanted to see the developments and Westernization movements that emerged in the following years as a transitional necessity, when he came to the conclusion that this was not the case, he openly criticized them in Javidname and expressed his regret. According to Iqbal, turning to the West with an imitative understanding is to move away from oneself. However, despite all these statements, Iqbal is ultimately ambivalent about the Turks. On the one hand, he criticizes secularization and Westernization, and on the other, he hopes that this process will end with a return to true Islam. As a matter of fact, in response to Nehru’s statement that the Turks had abandoned their religion and embarked on the path of progress, Nehru stated that “the Turks did not give up their religion, on the contrary, they turned towards a truer Islam”.

MEHMET S. AYDIN

(summary of TDV Islam Encyclopedia Muhammad Iqbal article)

He completed primary school with three classes and one teacher at the age of 14, sometimes attending and sometimes taking breaks. In the same years, İskender Efendi, the Mufti of Batumi, who had fled Stalin’s persecution, was working as an imam in Akyazı and he had the opportunity to benefit from him.

In 1956, he started Çorum Imam-Hatip School. Here, at the same time, he read and taught himself the textbooks read in the Madrasahs.

He continued to read East-West classics. He became acquainted with the works of Ibn Khaldūn. In the same years, he met İzmirli İsmail Hakkı, Seyyid Bey, Ömer Nasuhi Bilmen, Ahmet Nâim and Muhammed Hamdi Yazır. Some of the works he read had not yet been read by his teachers. He wanted to make up for the years he had to interrupt his studies. In those years, the Higher Islamic Institute had not yet opened. Ankara University Faculty of Theology also did not accept Imam-Hatip graduates. When the Democrat Party came to power, Imam-Hatip Schools were established in the first year of their rule (1951) and Istanbul Higher Islamic Institutes in 1959.

He attended Süleyman Uludağ’s Istanbul Higher Islamic Institute. During the years he lived in Istanbul, he had the opportunity to reach some of the last links of Ottoman relics: Nevzat Ayasbeyoğlu (1966), Ömer Nasuhi Bilmen (1971), Mahir İz (1974), Nihat Sami Banarlı (1974), Hilmi Ziya Ülken (1974), M. Tâvit Tancî (1974), Ali Nihat Tarlan (1978). He also had the opportunity to meet and listen to Muhammad Hamîdullah, Zeki Velîdî Togan, Mümtaz Turhan, Nurettin Topçu and Necip Fâzıl Kısakürek.

In these four years, he remained at an equal distance from all Islamic sciences and devoted equal time to all of them. He was interested in philosophy and theology as well as hadith and fiqh. His graduation thesis was on “Semâ”. He was more interested in the contemplative and philosophical aspects of Sufism.

After graduation, he was appointed as a vocational courses teacher at Kastamonu Imam-Hatip School. In the same year, he won the first prize in a translation contest organized by the Journal of Islamic Thought published in Istanbul.

He was then appointed to Kayseri Higher Islamic Institute and then to Bursa Higher Islamic Institute. The book writing and translation activities started in Kayseri continued. Especially with his translations, he introduced Turkish readers to the classics of Sufism: Kushayrî Risalesi, Istanbul, 1978, Kashf al-Mahjûb/The Knowledge of Truth, Istanbul, 1982 , Taarruf/Taufr in the Age of Birth, Istanbul, 1979 , Tezkiret al-Awliyâ, Bursa, 1984 , Şifâü’s-Sâil/The Nature of Sufism, Istanbul, 1976 , Faysalü’t-Tafrika/Tolerance in Islam, Istanbul, 1972, Esrâru’t-Tawhîd/The Secrets of Tawhidin, Istanbul, 2002.

In addition to these translations from Arabic and Persian, he gave importance to the simplification of Ottoman works in order to facilitate research on the history of Sufism and to transfer Sufi culture to new generations. The book Nefehâtü’l-Üns, a book of tabât/biography written by Molla Câmi and translated into Turkish by Lâmi’î Çelebi of Bursa (v. 1531), was translated into new letters for this purpose: Evliyâ Menkıbeleri, Istanbul, 2000. Kâtip Çelebi’s (v. 1656) publication of Mîzânü’l-Hakk (Mîzânü’l-Haqq ) under the title The Method of Criticism and Discussion in Islam was also aimed at creating the same cultural environment (the last two works were prepared together with Mustafa Kara).

Süleyman Uludağ’s specialization is the History of Sufism, but due to his deep knowledge of the basic Islamic Sciences, he has given lectures in fields other than Sufism and has written works on many subjects from economics and politics to philosophy and art: A New Perspective on Interest in Islam, Istanbul, 1988, Islam-Politics Relations, Istanbul, 1998, The Structure of Islamic Thought, Istanbul, 1979, The Wisdom of the Commandments and Prohibitions in Islam, Ankara, 1988, Mûsikî and Semâ from the Perspective of Islam, Istanbul, 1976 , Mürşid and Irşad Faaliyeti in Islam, Istanbul, 1975, Issues of Belief in Islam and Sects of Belief, Istanbul, 1992.

As part of his interest in Ibn Khaldūn, he translated the Muqaddimahand al-Sātī al-Husrī’s (v. 1968, Baghdad) Studies on Ibn Khaldūn. His introduction and footnotes to the Muqaddimahare rich enough to warrant a separate study (vol. I Istanbul, 1982; vol. II Istanbul, 1983).

One of his areas of interest is theology and philosophy. His works are taught as textbooks in Imam-Hatip Schools. He translated Taftāzānī’s Sharh al-Aqā’id, one of the basic books of madrasas and one of the classics of theology, under the title The Science of Kalām and Islamic Aqā’id (Istanbul, 1980).

His work in the field of philosophy of religion is a translation of Ibn Rushd’s Faslu’l-Maqāl and al-Kashf an Menāhij al-Adille, which he wrote to reconcile philosophy and religion: Felsefe-Din İlişkileri, Istanbul, 1985. Published in Nesil Magazine, January-February 1978, 4 and 5. Ibn Khaldūn’s Philosophy of Religion were published in their issues.

Suleyman Uludag, first and foremost Sufism and its History, Ankara, 1976, (with Selçuk Eraydın, Mehmet Demirci, Kâmil Yaylalı), Dictionary of Sufi Terms, Istanbul, 1991, Women in the Eyes of Sufis, Istanbul, 1995, Sufism and Man, Istanbul, 2001, has authored many works, and his articles are Generation, Movement, It has been published in many different journals such as Dergâh, İslâmiyât, İslâmî Araştırmalar, Köprü, Türkiye Günlüğü.

Süleyman Uludağ still teaches at the Faculty of Theology at Uludağ University, where he is currently retired, continues to train his students and continues his scholarly studies.